While the mozzies and no-see-ums sucked my blood, the heavy heat was sucking the life force out of Jase. Impeccably located, the Piramide Inn Resort on the Yucatán Peninsula gave us respite from the heinous level of humidity alongside a reprieve from the unyielding insects—cue an air-conditioned room. Who knew, you can even haggle over cold air! The hungry blighters were driving virtually every square inch of me to distraction and the equally insane temperatures were melting Jason’s face like hot wax dripping from a candle.

Chichen Itza beneath the sun’s first smile

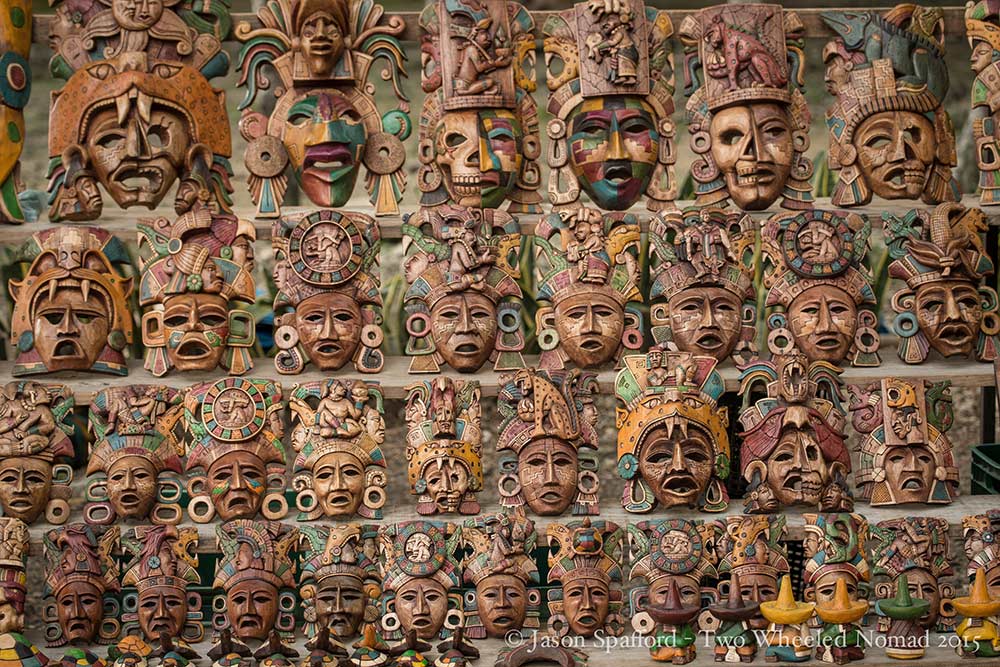

A vendor selling his handcrafted wooden wares at Chichen Itza

Moreover, leaving a crime-scene of Jason-shaped sweat all over his sleeping mat each morning told me a good night’s slumber in cooler climes might be just what the forensics would order. One of these mornings, he’d flood us from the inside out. Besides, it’s time consuming having between six to nine showers per day, eh Jase?! I too felt his sticky suffering and teetered on my side in a vain attempt of trying to minimise my body’s surface area touching anything else. Bartered down, price agreed and done. The lodging also happened to be a hop, skip and a jump-start on the bike from the pre-Hispanic city of Chichen Itza.

Mysterious masks on sale

By around 10am-ish, folks were filling up the Mayan tourist attraction like expanding foam seeps into every cubic inch of a hole. Including vendors flogging everything with a Mayan and, or Mexican reference: traditional dress and printed tees; woven fabrics, bedazzled sombreros and bags; Mayan calendars and magnets; pyramids in every conceivable material under the sun as well as whistles giving rise to an uncannily convincing, if not startling ‘big cat’ cry.

You’ll be spoilt for choice if you’d like a mask at Chichen Itza

My eyes and pace lingered when I came upon the only artefacts not a major player of the myriad tat; beautifully carved jaguar heads and handcrafted Mayan masks. Made from a local wood and stained with natural materials from the indigenous plants and flowers in a matte finish, we had to think twice about actually buying one. I’d never seen a mask so visually striking with such an arresting attention to detail. And collectively, they drew admiration and awe.

One of my favourites was the mask on the far right – amazing piece of artwork!

Rising with the roosters paid dividends in maximising the solitary experience at Chichen Itza—undisturbed by the swarming tourist throngs and masses of Mexican kids who’d recently broken up from school for the holidays. No blame culture in play, I just didn’t fancy being engulfed by a sea of them whilst trying to become ruined on the Mayan remains. Who would?

Stone carvings

As a UNESCO World Heritage site, Chichen Itza—excavated in 1841—was later accorded with the honour of becoming one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World. The empire was established from 750 to 1200 AD and situated close to two cenotes (natural cavities), from which the town took its name “At the edge of the well of the Itzaes”. The cenotes facilitated tapping into the underground waters of the area where the great city’s only reliable water supply was the series of sinkhole wells.

Spanish records report that young highborn girls were flung into the largest of these, alive, as sacrifices to the Maya rain god thought to live in its dark depths. Whoa, I hope it rained cats and dogs afterwards each time. Archaeologists have since found their bones, as well as the jewellery and other precious objects the sacrificial lambs wore in their final hours. Some of the high ranking prisoners met the same fate.

Strike a pose!

Throughout Chichen Itza’s nearly 1,000-year history, different peoples have left their mark on the sacred city including the Toltecs—who invaded and executed a merger of the two populations. The Mayan-Toltec vision of the world and the universe is revealed in their stone monuments, serpent-adorned balustrades, columned arcades and other artistic works—intimately tied to what was visible in the foretelling night skies above the Yucatán Peninsula. The fusion of Mayan construction techniques with aspects from central Mexico makes Chichen Itza perhaps the chief example of the Mayan-Toltec civilization in Yucatán.

Incredible detail within the stone carvings

Amid the sacred structures that survived, the most recognizable structure was the Temple of Kukulkan (or El Castillo). This glorious step pyramid demonstrates the accuracy and significance of Maya astronomy—and of course the heavy influence of the Toltecs. The temple had 365 steps—one for each day of the year. Devising a 365-day calendar was just one of a timeless number of feats of Maya science.

Amazingly, twice a year on the spring and autumn equinoxes, a shadow falls on the pyramid in the shape of a serpent. As the sun sets, this shadowy snake descends the steps to eventually join a stone serpent head at the base of the staircase. The Maya’s astronomical skills were so advanced they could even predict solar eclipses; the impressive and sophisticated circular observatory, El Caracol for instance, remains on the site today.

Peeking out around the warrior pilasters

Chichen Itza was much and more than a religious and ceremonial site. It was also a hub of regional trade and highly established urban centre. Chichen Itza’s ball court is the largest known in Mesoamerica, measuring 168 metres long and 70 metres wide. During ritual games here, players tried to hit a 5-kilogram rubber ball through stone scoring hoops set high on the court walls using their hips and sometimes elbows. Competition was fierce as losers were put to death. Spectator sports are not usually my thing but count me out for this game. But after centuries of prosperity and absorbing influxes of other cultures, the city met a mysterious if not curious end.

-

I want them all! Collectively, the masks look amazing

Come early afternoon, so too did our self-guided tour of Chichen Itza. It was time to marvel at the sacredness of Maya ruins no longer but swop them for the soothing waters of the cenotes. As deep natural wells or sinkholes go—formed by the collapse of surface limestone that exposes ground water beneath—I couldn’t seem to get my fill of them.

Chichen Itza is well worth a nosy

Some of the pyramids will knock your socks off, they did me

The Maya called the cenotes ‘dzonot’ so we zoomed 20 minutes up the road from the Piramide Inn Resort near the colonial town Valladolid to one called Dzitnup. Driving inland through Mexico around the Yucatán, we were hit by a succession of uneventfully straight roads, frightfully featureless landscape of no hills—the few there were aren’t exactly lofty—and a noticeable lack of major rivers. The rivers were present and in abundance, just underground—channelling through the nooks and crannies and caves and caverns all made of porous limestone. The Yucatán is indeed pockmarked like the hollows of Edam cheese with about 3,000 sinkholes, around only half of which have been documented.

Cooling down in a sparkling cenote

Visually striking is what struck our eyes at Cenote Dzitnup, perhaps one of the prettiest sinkholes we’ve seen too. As neat and natural underground oases go, this one was not to be missed. Set in two limestone caves with a single opening in the ceiling to each, enabled shafts of light to shine over the natural beauty of the water and place. I bent over to look at my reflection in the mirrored surface.

Testing the water with a finger, I found it cool; wading in, the water’s bite invigorated my skin as I settled in the sunlight before dousing my head. I felt clean and fresh and my skin tingled. Head half submerged, I peered up keeping my ears below the waterline and saw scores of small fruit bats nestling as they nested on the ceiling, while the black catfish frolicked in the plant life directly below me.

Stunning light shines down into the cenote

The fresh water cenotes have been meticulously filtered by the earth, making them so clear and pure that we could watch when finger-sized fish nibbled on our feet. Limestone formations arched spectacularly over the water, enveloping us within another one of those body-delicious experiences in a unique and atmospheric underworld. It was a secret spot of emerald green and turquoise pools, and I wondered if the same gods to which the Mayans spoke and sacrificed were listening. The dead skin on my feet was about all I could offer, and I hoped that would suffice.

We dodged the scorching sun until dusk, swimming in crisp, vitamin- and mineral-rich waters—meant to nourish the skin. Heaven sent. It was akin to an aquarium in high-definition where ancient tropical trees and vines created wild cathedral walls leading up to shafts of sunlight bursting through an opening in the ceiling; easy to see why the cenotes held the Mayans in awe. They did me.

Time for a midday snack

Sounds like a nice place to visit!

LikeLike

I was there 12 years ago and was able to climb to the top of the pyramid and walk all around. It looks like it’s closed now. Is it closed forever or just temporarily?

I love the photo of you looking up at the pyramid.

LikeLike

Cheers George, I’m used for scale so you know, do my bit! Think it may be closed indefinitely for preservation, fair enough. L

LikeLike

Glad to see you enjoying the entrancing sites! The masks are amazing works of art. Do you buy souvenirs along the way? Do you ship them back home?

You said, “after centuries of prosperity and absorbing influxes of other cultures, the city met a mysterious if not curious end.” Maybe they insensibly played ball too often and died of attrition. :o)

I love the photos so I pinned a couple more of them onto my Pinterest page (www.pinterest.com/mariollige/dynanim-explore-energise). Where are the ones of you both jumping across a cenote on your bikes?

LikeLike