We almost changed our minds about visiting Harberton Estancia, a sheep farm. Glad we went ahead; we came upon the working ranch, which was founded by Thomas Bridges naming it after his wife’s home village, Devon in the southwest of England. Orphaned at thirteen, he was named Thomas Bridges having been found with a ‘T’ embroidered onto his T-shirt in 1856 under a bridge on Keppel Island on the Falklands. By 1871, Thomas was Head of the South American Missionary Society and with his family became the first white settlers to inhabit Ushuaia.

Harberton Ranch

The main residential property we saw on the sheep farm was actually constructed in Devon back in the nineteenth century; the individual house pieces numbered and dismantled before being shipped across the Atlantic for three months to be rebuilt on Tierra del Fuego. That – coupled with ‘Made in England’: farming equipment, top to bottom house contents, sheep and flora made for a settlement priding itself on a serious appreciation of English culture, customs and long-standing traditions.

Part of a beautiful mural depicting the Yamana people.

More interestingly, Thomas Bridges unlike many, successfully integrated with the natives, the Yámana, a Fuegian tribe of coast-hugging sea nomads. Thomas was young enough to learn Yahgan and went onto to write a 30,000 word dictionary of the indigenous language. It was altogether disheartening to learn that the Yámana and other Indian tribes had lived in harmony for centuries until the Europeans arrived in the 1800s. Since that time, the Europeans and Americans hunted down whales and seals, depleting the tribes of their energy-rich food sources. In the last thirty years of the nineteenth century, the Yámana were decimated by European diseases. Perhaps one of white man’s biggest social failings. Today, only one person remains, Cristina Calderón – who can speak the native tongue.

Although well into the winter of her days, she is also the last full-blooded Yámana. What we wouldn’t give to interview that uniquely special lady. The fourth generation ‘Tommy’ now eighty lives on the estancia today alongside his wife Natalie Prosser, founder and director of the museum based on world-renowned study of marine mammals and birdlife. Boasting over 2,000 untreated skeletons for live research purposes, including near-perfect specimens such as Crab eater seals and Commerson’s dolphin, we were just as enlightened over the whales’ skeletons especially the beaked variety; Gray’s, Shepherd’s and Hector’s to name just a few. The strap-toothed whale, also known as the Layard’s beaked whale was probably one of most flamboyant examples of Mother Nature’s imagination; the male of these mammals develops strap-like teeth that curve around right over its upper jaw; they curled to such an extent that it prohibits full range of jaw movement.

Using Jason for scale against some whale skulls.

This is believed by scientists to attract a mate, even if it does mean this marine mammal can only suck in and slurp its food. Au fait with many sea creatures, we’d never even heard of most of these genera before. I was fascinated by the fact that only Tierra del Fuego in the southern hemisphere dips into one of the world’s strongest currents, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current washing up on a daily basis marine carcasses that experts know so little about and on occasion nothing at all. Scientific study is constantly undertaken off these shores, if only our credentials were a little more biology-oriented and bi-lingual, we would’ve volunteered in a heartbeat.

Tierra del Fuego incidentally was named from a Spanish expedition circumnavigating the world led by Portuguese Fernando de Magallanes; he discovered the Strait of Magellan in 1520 and marvelled at the countless fires that burnt day and night on a piece of land to his left, christening it Tierra del Fuego, the Land of Fire. During our time on the Land of Fire – we climbed a glacier to capture some aerial footage with Andrew, an American guy staying at our hostel with whom we’d gelled. The glacier, which was 825 metres in imposing height required a certain ‘mountain goat’ approach to scramble up the scree at its steepest parts.

It felt good to thread our way up; rosy-cheeked and pulse pumping, we reached the top onto the saw-toothed and jagged ridges. We took our time up there, didn’t spot a single fire before having to carve into if not ski back down the scree. In the meantime, trigger-happy with the cameras, panning the GoPros around on rods and flying one above us devoured the early afternoon. We hankered after the power shots knowing that good light on a landscape is usually ephemeral, it is, in short luck! Yet it didn’t take too much skill to get them; the formidable Martial Mountains bathed in a gentle, pretty light amply lent themselves to these. Peering over the sheer glacial face, we spotted our first black and white condor – effortlessly gliding below us through the autumnal valley aglitter in what seemed like half a hundred colours.

Leaves in all the colours of autumn.

It was much later when we re-watched some footage we shot in Tierra del Fuego’s National Park of a Pygmy owl perched on a nearby branch, did we notice that when her head spun 180 she revealed a second pair of eyes. The pattern in her feathers projected a harrowing blackened stare to any likely predators. Nature’s fauna is incredible, not to mention the captivating gardens within the micro flora we protectively tiptoed around back down the glacier within the Martial mountain range. The iron-filled rocks bearded with dark green lichen enraptured Jason. Perfect time to gulp down some clean air, packing our lungs before inhaling those wretched exhaust fumes in and out of cities all too soon.

Jason on the Martial glacier.

With time on our hands, fuel in our tanks and a brightly burning flame of desire to explore the island, we revisited Harberton Estancia. For the first time in the southern most part of the world, it had begun to snow; the flurry from which soon turned to face-stinging hailstones. Within twenty-four hours, temperatures had hurtled from a sunny fifteen degrees Celsius down to a biting one degree. Lashing hail turned into blowing rain, hammering hard against us. There was a nasty wind chill on top but the real enemy was the cold. It was like a knife cutting right through our warmest thermals. It steals up on you quieter than a shadow, and at first you shiver pulling in your neck like a turtle.

Your teeth chatter and you curl your toes imagining the sensation of swallowing mulled wine in front of the fire. It burns it does. Nothing burns like the cold. But only for a while. Then it gets inside you and starts to fill you up, and after a while you start to lose the strength to fight it. It’s easier to lie down or go to sleep. I wondered if you completely let yourself unto it, the pain would disappear on its own accord. I could almost see myself giving into it, everything kind of fading like sinking into a bath of warm milk. Peaceful, like. I snapped myself out of it. I was ridiculously cold but refused to give in. What was ridiculous was that I’d forgotten my heated jacket.

see no evil…

Back at Harberton’s ranch, we retreated from the bitter weather and my restored core body temperature revived my ice blocks for feet and icicles for fingers. We were surprised with an extensive tour of the laboratory, given an unexpected free lunch and an afternoon harmoniously exchanging stories with the volunteers studying marine mammals. They were as interested by the sealife we’d previously seen scuba diving by us learning about the research conducted on the same oceanic animals. En route back to where we were staying, the interchangeable ‘four seasons in one day’ took a respite and allowed us to take a small detour over to Garibaldi Pass; Jason had a glint in his eye, which usually meant one thing:

Outside our favourite haunt for a coffee.

“Fancy a spot of off-roading Lise?” “Mmmn, may be….”, I pondered while surveying how technical the terrain looked. “Come ooon”, came a surge of encouragement, “the snow is only a light dusting up that steep hill…and just watch out for those big rocks when crossing the water”. I went for it with an unusual gung-ho gusto, dipped my big toe in and came out the other end, bike still upright, feeling exhilarated if not a tad shaky from a spike of adrenaline. What a thrill – the best things in life are free.

On the road to Harberton Estancia.

That evening we were invited to join Juan Pablo at his weekly motorcycle meet. It tickled us that no one out of the forty or so there had ridden their bikes to the venue. Well it was practically winter – I guess no one felt the need to be martyrs including us. I thought we’d be in store for a few hours of conversation stationed at a quiet corner of a pub. Little did we know that we were to be regaled with a three-course homemade meal washed down by a bottle of Argentina’s finest Malbec and the opportunity to mingle with many. The divine part of my soul with my conscience, restraint and desire to ‘do good’ gave way to the animal side of my soul; my appetite for food; for drink and in this instance lust for meat. I ate with fervour and satiated an unabashed appetite.

The old post office found in Tierra del Fuego National Park.

By the wee hours, we had yet again been on the receiving end of the warmest reception that is Argentinian hospitality – the peak at which extended to an invitation to join a group of local motorcyclists on a remote, extra fuel carrying off-road biking trip. Before I knew what we’d signed up for, there was a roar of ardent agreement to our participation. Juan Pablo had orchestrated our being a part of all this. He had a quiet, unassuming way about him but I couldn’t help notice his punctilious ease of manner towards Jason and me.

There seemed to be no bounds to this guy’s willingness to help and open up the real Tierra del Fuego to us. We were being opened up to his culture in a very exposed way that provided not just a new experience but personal growth as well. I was increasingly beginning to feel and understand the essence of why we should all travel. The weeks in Ushuaia on Tierra del Fuego were bathed in my mind in a permanent glow. Alas, it was time to go.

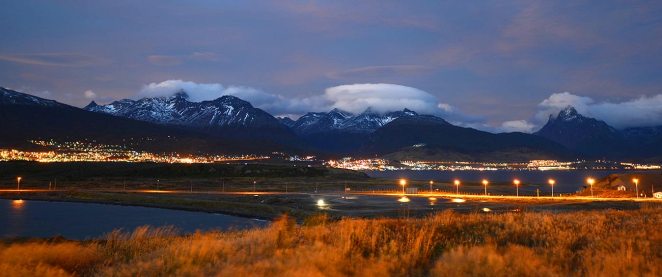

Ushuaia by night.

I look forward to your stages and this one had great history of where you are. Thanks very much.

LikeLike